Michael T.M. Emmerich

Date: 2025-12-29

Abstract

It is Christmas time: books appear in cheerful piles as gifts, and in some households the morning after brings not only a “hangover” but also an ambitious attempt to stack them and exploit “overhang” beyond the edge of a table. How far can a stack of identical “books” (idealized as rigid, frictionless blocks) extend beyond the edge of a table without toppling? We also provide a small Python game in which you can test your book-stacking skills: it implements the mechanics described here as interactive code and is linked from the essay [4].

1. The setup (what “x” means)

We model each book as a rigid block of length and weight

.

Everything happens along one horizontal line, so the only coordinate we use is

, measured in book lengths.

The table supports everything to the left of its edge:

A block is the interval

, so

is its left endpoint.

Its center of gravity is

.

We allow only vertical forces (no friction, no horizontal forces).

A configuration is balanced if each block satisfies force equilibrium and moment equilibrium with nonnegative support forces.

Endpoint reduction (key simplification).

If a block is supported on an overlap interval , then for equilibrium it is enough to replace any distributed support by two endpoint forces at

and

.

If the total upward force is

and the resultant acts at position

, then the endpoint forces are

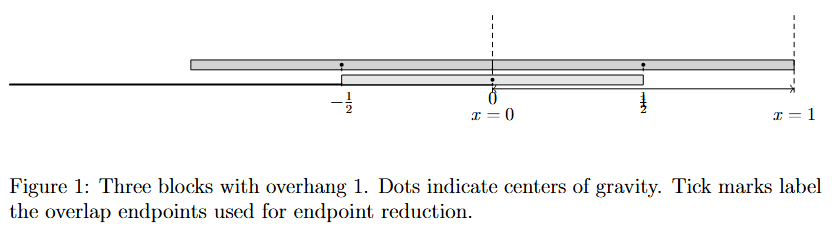

This is why the figures mark endpoints: those are the only places we need to “push up” in the model (Figure 1 and Figure 2).

2. Warm-up: three books, overhang 1

A small configuration (Figure 1) is

The rightmost edge is , so the overhang beyond

equals

.

The centers of gravity average to

, i.e., the stack’s center of gravity lies exactly above the table edge.

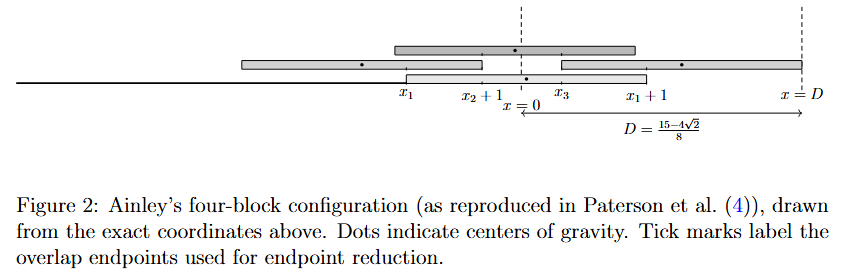

3. Ainley’s four-book configuration

A classical four-book arrangement due to Ainley [1], reproduced in Paterson et al. [2], achieves the overhang

, slightly better than

.

See Figure 2.

With table edge at , one exact coordinate description is:

The overhang is the right edge of :

4. The force-tree idea (magnitudes) and the endpoint geometry (positions)

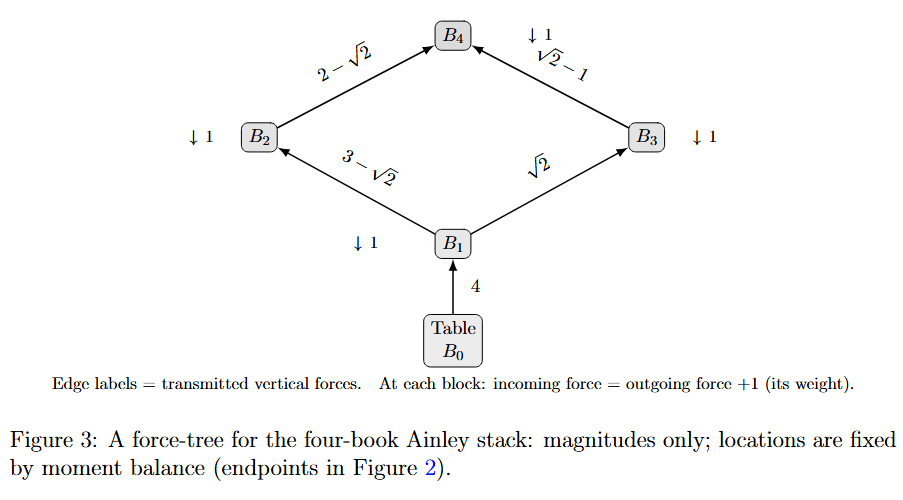

Paterson et al. [2] popularize a bookkeeping device: a tree of vertical force magnitudes.

Each book receives upward support from below, “spends” unit to hold up its own weight, and passes the remainder upward.

This explains why the numbers in Figure 3 add up so cleanly.

The tree gives only how much force is transmitted. To prevent tipping, we also need where forces act. Moment balance fixes these positions, and endpoint reduction lets us assume they occur at overlap endpoints—exactly the ticks shown in Figure 2.

5. Detailed vertical force balance for all four books (Ainley stack)

The force tree can make it look as if “all forces point upward.” In fact, each book experiences both upward and downward vertical force vectors.

In static equilibrium, each book has its weight as a downward force vector

acting at

,

and vertical contact forces at overlap endpoints.

For each book we require

(equivalently

).

Top book (supported by

and

):

- Upward vertical force vector at

:

.

- Upward vertical force vector at

:

.

- Downward weight force vector at

:

.

Force equilibrium: .

Middle-left book (supported by

, carries part of

):

- Upward vertical force vector at

:

.

- Downward weight force vector at

:

.

- Downward vertical reaction force vector from

at

:

.

Force equilibrium: .

Middle-right book (supported by

, carries the rest of

):

- Upward vertical force vector at

:

.

- Downward weight force vector at

:

.

- Downward vertical reaction force vector from

at

:

.

Force equilibrium: .

Bottom book (supported by the table, carries

and

):

- Upward vertical force vector at

:

(table on

).

- Downward weight force vector at

:

.

- Downward vertical reaction force vector from

at

:

.

- Downward vertical reaction force vector from

at

:

.

Force equilibrium: .

Moment equilibrium then fixes the positions

so that these endpoint forces are compatible with the overlap geometry (Figure 2 and Figure 3).

6. Force equilibrium vs. moment equilibrium (outer middle block in the Ainley stack)

Force equilibrium prevents vertical translation, but it does not by itself prevent tipping.

Moment equilibrium

is the “no rotation” condition: in this 1D geometry a vertical force of size

applied at position

has moment

about a reference point

.

Consider the outer middle-right book .

Its upward support is concentrated at

, and its two downward forces act at

and

.

Force equilibrium holds because

.

To see why

also does not rotate, choose the reference point at the support endpoint

.

Then the upward support contributes no moment, and the moment balance becomes

Equivalently,

This says that the combined downward load on has its resultant passing exactly through

.

That is why a single endpoint support force is sufficient: there is no net turning tendency about that point.

More generally, with support on

, moment equilibrium is the condition that the resultant lies within

; otherwise one endpoint force would have to become negative (impossible in the vertical-contact model), and the book would tip.

7. How the geometry determines the forces (and the moments)

In this vertical-force model, the geometry does not determine the force magnitudes by itself.

What geometry determines is where forces are allowed to act: a book can only be supported where it overlaps what is below.

The actual magnitudes then follow from two equilibrium laws on each book:

force equilibrium and moment equilibrium

.

Step 1: geometry gives allowable support points (endpoints).

If an upper book overlaps a lower book on an interval , then the lower book can exert upward vertical forces anywhere in that interval.

By endpoint reduction, we can replace any distributed support by two endpoint forces:

one at

and one at

.

This is where the “geometrical lengths” enter: they define

and

.

Step 2: force + moment equilibrium on one book (lever rule).

Suppose a book has a combined downward load of total magnitude whose resultant acts at horizontal location

.

If the book is supported on

by endpoint forces

at

and

at

, then equilibrium gives two equations:

Solving yields the endpoint forces

So force equilibrium fixes the sum , while moment equilibrium fixes how that sum is split between the endpoints.

Step 3: how to compute and

.

If downward forces act at positions

on a book, then

In particular, the book’s own weight contributes at

.

How this plays out in Ainley’s stack (one concrete check on ).

On the outer middle-right book , the downward forces are: its weight

at

, and the downward reaction from the top book of magnitude

at

.

Hence

and

Geometry says overlaps the bottom book on the interval

.

Ainley’s critically balanced choice of coordinates makes the resultant land exactly at the right endpoint:

.

Then the lever rule forces

and

,

i.e.,

is supported entirely at the single endpoint

—precisely the endpoint pattern shown in Figure 2.

8. Balance versus stability (a small reality check)

The configurations above are balanced: they satisfy equilibrium with nonnegative vertical reactions. Some are critical in the sense that forces concentrate at endpoints. A physical stack may need a tiny perturbation or a touch of friction to be robustly stable; this distinction is discussed in [2].

9. Try it yourself (interactive code)

A companion Pygame implementation [4] lets you experiment with the same mechanics. It works in pixel coordinates, but the mapping is conceptually simple: one book length in the paper corresponds to one book width in pixels. The game computes a resultant load position and routes it to bracketing overlap endpoints (an “endpoint-tree” implementation of the same model).

Appendix for nonlinear optimization readers

The full PDF version of this note contains an additional section that formulates Ainley’s four-block arrangement as a small nonlinear programming model (with endpoint-force variables) and checks KKT conditions for the classical Ainley solution. Readers familiar with nonlinear optimization may prefer that presentation; see the PDF linked in the references.

References

- S. Ainley, “Finely balanced,” Mathematical Gazette, 63 (1979), 272.

- M. Paterson, Y. Peres, M. Thorup, P. Winkler, and U. Zwick, “Maximum overhang,” American Mathematical Monthly, 116 (2009), 763–787.

- M. Paterson and U. Zwick, “Overhang,” American Mathematical Monthly, 116 (2009), 19–44.

- M. T.M. Emmerich, BookStacker (interactive Pygame trinket), https://trinket.io/pygame/f617e94d9da2 (accessed 2025-12-29).

- Wikipedia, “Block-stacking problem,” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Block-stacking_problem (accessed 2025-12-29).

- Full PDF version of this essay (with the NLP/KKT appendix), Maximum Overhang Report (accessed 2025-12-29).