Michael Emmerich, 12 July 2025

1. Introduction

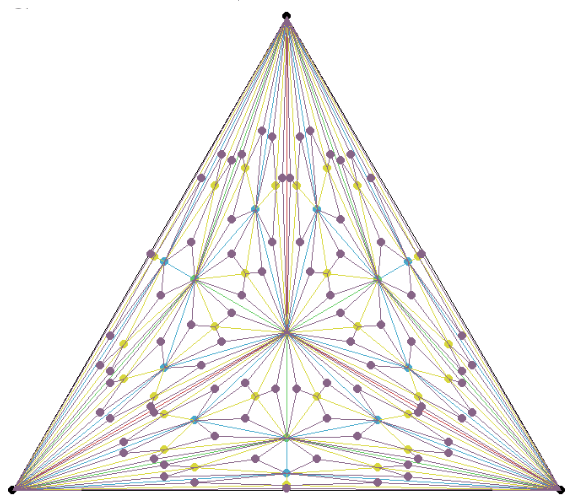

A single, easily stated geometric rule—“draw the centroid of a triangle, connect it to the three vertices, and repeat recursively on the new sub-triangles”—produces a surprisingly intricate picture. This short exposition introduces the construction, shows how recursion drives the emergence of symmetry and complexity, and points out why the pattern fails as a uniform space-filling scheme for a simplex. An accompanying interactive Python/Pygame demo is available at trinket.io/pygame/fa7317c8b912.

2. The One-Line Rule

Let be non-degenerate. Define its centroid

The centroid subdivision rule is:

Insert ; join

to

,

, and

; then apply the same rule to each of the three smaller triangles.

The only free parameter is the recursion depth .

3. Symmetry from Simplicity

Despite its simplicity, the pattern after levels displays

-fold rotational and

mirror symmetries—the full symmetry group of the original equilateral triangle if one starts with

equilateral. Such “complex symmetry from basic rules” echoes themes in cellular automata, recursively defined computer graphics such as L-systems (Prusinkiewicz, P., and Lindenmayer, A. (2012)), and other studies of emergent phenomena in complex systems.

4. Recursion & Fractal Flavour

Each recursion step multiplies the number of triangles by three, so after depth we have

The edge length scales by a factor at each level, suggesting a Hausdorff fractal dimension

Although the drawing remains a subset of the original triangle (thus

), the visual density quickly becomes “fat” enough to look area-filling to the naked eye. (See Mandelbrot 1982 for further reading on fractal dimension).

5. A Space-Filling Attempt That Falls Short

The original motivation was to create a centre-oriented, uniformly space-filling refinement of a simplex which would be useful in optimization algorithm design (e.g. Pang et al. 2023). However, centroids are not evenly spaced: points cluster near the centre while the three outer “petals” remain sparse. Quantitatively, the point density , measured as a function of distance

from the triangle’s barycentre, is sharply peaked around a ring at roughly

. Thus the subdivision is a striking illustration that symmetry does not guarantee uniform distribution.

6. Why It’s a Friendly Programming Exercise

- Short code, rich output: fewer than 50 lines of Python generate a picture that invites endless zoom-ins.

- Clear correspondence: each line of code maps to a single geometric idea (centroid, edge list, recursion).

- Real-time graphics: Pygame lets students watch recursion unfold level by level, reinforcing otherwise abstract call-stack notions.

- Adaptable: tweak colours, add animation, or export to vector graphics—all without touching the core algorithm.

7. Try It Yourself

Run the interactive standalone python source code and demo online:

https://trinket.io/pygame/fa7317c8b912

Use the \texttt{SPACE} key (or wait a few seconds) to add subdivision levels; watch the point counter climb and notice how quickly the centre densifies compared to the corners.

Conclusion

From a simple centroid subdivision rule emerges a tapestry of straight lines, self-similar triangles, and fractal geometry. The construction serves equally well as a gentle gateway to recursion for beginners and as a small case study in how complex, symmetric behaviour can spring from spare instructions—a recurring ‘leitmotif’ or theme across the study of complex systems.

Ackknowledgement

This essay and the subdivision algorithm was inspired by a discussion with Lie Meng Pang and Hisao Ishibuchi during their visit to Finland in July 2025.

Further Reading

[1] Mandelbrot, B. B. (1983). The fractal geometry of nature. Freeman, New York. (on fractal dimensions)

[2] Prusinkiewicz, P., & Lindenmayer, A. (2012). The algorithmic beauty of plants. Springer Science & Business Media. (on recursive geometries)

[3] Pang, L. M., Nan, Y., & Ishibuchi, H. (2023, October). How to Find a Large Solution Set to Cover the Entire Pareto Front in Evolutionary Multi-Objective Optimization. In 2023 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics (SMC) (pp. 1188-1194). IEEE.

Python Source: Minimalist Implementation

import math

def centroid(A, B, C):

return ((A[0] + B[0] + C[0]) / 3,

(A[1] + B[1] + C[1]) / 3)

def subdivide(A, B, C, depth):

if depth == 0:

return set(), set()

D = centroid(A, B, C)

points = {D}

# store edges with sorted endpoints to deduplicate

edges = {(tuple(sorted((A, D))),),

(tuple(sorted((B, D))),),

(tuple(sorted((C, D))),)}

if depth > 1:

for P, Q in ((A, B), (B, C), (C, A)):

pts, edg = subdivide(P, D, Q, depth - 1)

points.update(pts)

edges.update(edg)

return points, edges