Michael Emmerich – 29 June 2025

1. Introduction

Positive integers and their fundamental building blocks, the prime numbers, exhibit a rich combinatorial structure. This essay is part of a series that aims to derive some of the intriguing properties of integers using only elementary mathematical tools, thereby making them accessible to a broader audience. We do this by adopting the prime-vector representation (Emmerich, 2025), in which rational numbers can be placed naturally on a grid whose axes correspond to prime bases and their exponents. In this picture, number theory becomes a combinatorial game of rearranging positions on the grid and counting possibilities.

In this essay, we revisit the fundamental notions four: coprimality, divisibility, and the arithmetic functions that measure them, in particular the Euler totient function, through the lens of representation of the prime vector (Emmerich, 2025). By recasting every positive rational as a vector of prime exponents, arithmetic collapses to ordinary integer addition and subtraction of coordinates. Within this coordinate system

- coprimality and the totient function emerge as simple sign-pattern conditions on pairs of prime vectors;

- divisibility properties translate to component-wise ordering of vectors; and

- the divisor-counting function

becomes a lattice-point enumeration problem.

Special attention is given to Euler’s totient function, which has a nice interpretation in a group-partition scheme, which we will also employ to reprove Gauss’s sum of totients lemma. This lemma provides one interesting bridge between additive and multiplicative structures in positive integers.

2. Prime-Vectors

Let us briefly review the basics of the prime vector representation, as introduced in (Emmerich, 2025). Prime vectors are in several aspects a convenient representation of positive rational numbers. Prime vectors make it possible to handle rational numbers in their reduced form, using only integers in their representation, and to combine integers, as well as positive integers, multi-dimensionally by means of integer vector addition and subtraction. Let be the ordered primes. Every positive rational number

factors uniquely as

and is represented by its prime vector

with only finitely many non-zero entries. In this representation, multiplication and division of rational numbers can be reduced to integer addition and subtraction.

Lemma 1 (Component-wise operations) For all positive rationals

where the addition/subtraction is component-wise.

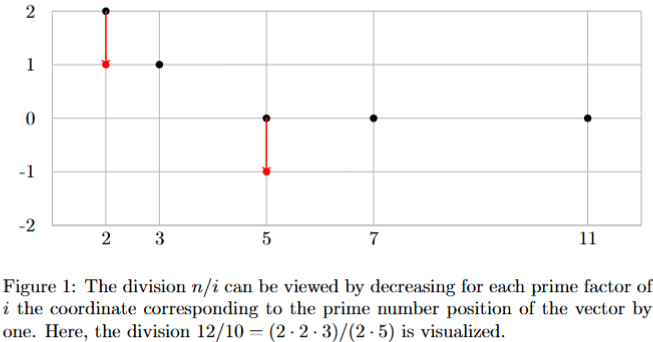

The beauty of this reformulation of integer division and multiplication is that these operations can now be naturally performed as simple geometric shifting operations on a grid with the coordinate axis being the prime bases and their exponents. See Figure 1 for an example.

Another notable advantage of the prime vector representation is that it encapsulates rational numbers in their simplified or reduced form, where the numerator is denoted by the positive component, and the divisor is denoted by the negative component (Emmerich, 2025). For example, the prime vector uniquely represents the fraction

.

Observe the analogy with logarithmic rules; however, in this framework, all computations are purely integer-based, avoiding the use of transcendental numbers altogether.

3. Divisibility

It is well known that all divisors of a positive integer can be constructed by combinations of its prime factors. Then it is easy to verify the following theorems that relate prime vectors to divisors.

Lemma 2 Letand

denote two positive integers with

then

divides

(in symbols:

, iff

, i.e. the difference of the prime vectors has only non-negative components.

and we can now find the set of all divisors.

Lemma 3 The set of all positive integer divisors of the positive integerwith

is provided by

and we can count the number of divisors by product:

.

Example: Let us find the divisors of . In the prime vector notation, 12 is represented as

. Thus we can find its set of divisors as

,

,

,

,

,

. And these are

divisors.

4. Co-primality

Co-primality can be regarded as the conceptual antithesis to divisibility. In this context, the focus is on identifying integers whose sets of prime factors exhibit no commonality.

Lemma 4 (Coprimality criterion) Letand

be the prime vectors of two positive integers. They are co-prime if and only if their positive coordinates do not overlap, that is:

Example. Let

and

. Then:

and their positive coordinates are in disjoint positions. Hence,

and

are co-prime.

In contrast, let

, so

. Then

and

both have positive entries in the same indices, so

and

are not co-prime.

Corollary 5 (Sign pattern of the difference) For coprime integer vectors,

is exactly positive at the coordinates where

is positive and negative exactly where

is positive.

Equivalently,

Remark 1 Observe that the positive part of a prime vectorwhich we denote with

can be interpreted as the prime vector of the numerator, while the analogously defined negative part of a prime vector

denoted with

serves as the prime vector of the divisor in the simplified fraction

. Take, for example, the vector

, which corresponds to the fraction

.

Example. Using the co-prime and

from above:

5. Euler’s totient function

Euler’s totient function counts how many positive integers smaller than

are relatively prime to

(that is, co-prime). Its deceptively simple definition conceals a web of deep connections: It drives Euler’s theorem and the RSA cryptosystem, linking multiplication and addition through prime factors and divisors, which themselves can be viewed as recombinations of the main constituents of a number.

Definition 6 (Euler’s totient) For a positive integerthe Euler totient is defined as

with

being the largest common divisor.

The arithmetic function was studied systematically by Euler (cf. Euler, 1763); the noun totient was introduced by Sylvester according to (Tou, 2017). It turns out that Euler’s totient function can be computed using a remarkably simple formula, which follows directly from the elementary number theory (see, e.g., Wilson, 2020).

Lemma 7 Letbe the prime factorization of a positive integer

. Then:

Proof: The totient function counts the number of positive integers less than or equal to

that are co-prime to

.

Let us first compute the formula for the totient of a prime power:

We are counting the number of integers that are coprime to

. The only integers not coprime to

are those divisible by

, i.e., the multiples of

up to

. In total, there are

such numbers. Therefore, the count of integers coprime to

is:

. Since the totient function is multiplicative for coprime arguments, we have:

as claimed.

6. Euler’s Totient Function from a Prime-Vector Perspective

We now characterize Euler’s totient function in terms of prime vectors. Fix a positive integer . For each

, define the prime vector difference.

Then if and only if

i.e., the positive part of the vector difference recovers the original vector . This leads to the following alternative formulation of the totient function:

Corollary 8 (Totient count via prime vectors) Let. Then:

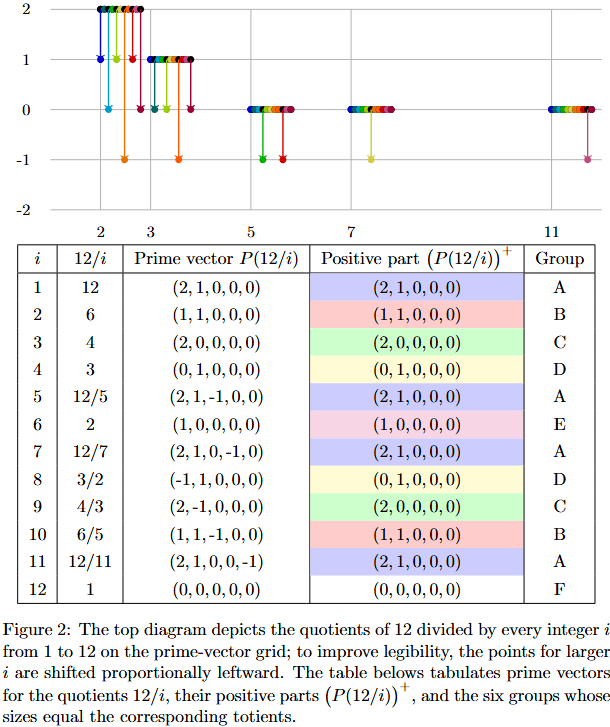

Example: For in Figure 2, we compute all values

and group them by their positive parts

. The group

is the subset with the property

and its size is the value

.

This structure reveals a natural path to Gauss’s classical identity:

Theorem 9 (Gauss’ sum of totients identity) For every positive integer,

Before stating a proof of this theorem, which was first proved by Gauss (Gauss, 1801) let us look at an example.

Example: Let us looking at the sum of totient rule for the example where in in Figure 2 we form groups by positive parts of the prime vectors of

,

.

| Group A | |

| Group B | |

| Group C | |

| Group D | |

| Group E | |

| Group F | |

Adding the group sizes reproduces

, exactly as Gauss’s theorem predicts.

Let us now proof Gauss’s sum of totient identity by making some use of prime vector notation. Let be the prime vector of

. For each

, define the row (as in Figure 2:

Note that the unique prime vector representation of the reduced-form rationals ensures that all rows are distinct (see (Emmerich,2025)), so we get exactly distinct rows.

Group the rows by their fourth entry, the positive part . This yields a partition.

of the index set .

Each block can be associated with a divisor

; The divisor is given by

and it is easy to verify that

is a divisor, since

, componentwise.

Lemma 10 shows that the size of a group is associated with the divisor

of

precisely is the totient of

, in other words

.

Lemma 10 (Lemma on Group Sizes) For a blockchoose any index

and set

Then

.

Proof: Firstly, let us explain why a group is at least the size of the number of coprimes of to

. Fix the group and

. The complete set of integer divisors is

, and includes the numbers

. We can now perform the divisions

in two steps as illustrated below:

The first step is to divide by

and we obtain

. then we divide by

to obtain

,

, and only in the case where

is a co-prime

we have

.

Let us now argue why no additional elements to the ones discussed above can join the group : Let us consider two cases for

:

Firstly, consider . In this case

with

being an integer that due to the definition of

is not coprime with

. Hence, when dividing

we do not get

.

Secondly, consider the other case, that is, . Then it is also impossible to get

because

and

consists of only positive integer components and

. Thus, we conclude the proof of the auxiliary lemma.

The sum of totient lemma follows from the auxiliary lemma and the fact that the group sizes sum up to , as each prime vector

,

belongs to exactly one of the groups.

The foregoing argument closely mirrors the classical proof that counts reduced fractions. However, expressed in prime-vector language, every rational automatically appears in lowest terms because each exponent is split into its positive and negative parts. This coordinate-wise view might make the divisibility reasoning more transparent.

7. Conclusion

Expressing numbers in prime-vector form makes questions of divisibility and related prime-number properties surprisingly transparent. In this framework we were able to give elementary derivations for criteria of coprimality, the divisor function , and Euler’s totient

.

So far, however, prime-vector notation has not produced decisively simpler proofs of the deeper results about , nor has it resolved the classic open problems of prime-number theory. A striking example is Carmichael’s conjecture, which asserts that every value taken by~

is attained by at least two distinct integers —a statement that remains unproved.

Computer science reminds us that choosing the right data structure can turn an opaque problem into an elegant algorithm. By analogy, refining number representations that are tailored to arithmetic structure may yet unlock new methods for studying the positive integers. Pursuing such representations — and the combinatorial reasoning they invite — therefore appears to be a promising direction for further research.

References

Emmerich, M. T. M. (2025, January 12). On prime vectors and unique factorization of rationals. Mathematical Playground. http://www.emmerix.net

L. Euler, Theorematum quorundam ad numeros primos spectantium demonstratio (A proof of certain theorems regarding prime numbers), Commentarii Academiae Scientiarum Petropolitanae 8 (1741), 141–146. Eneström index E54. Latin original and an English translation by D. Zhao available at the Euler Archive.

L. Euler, Theoremata arithmetica nova methodo demonstrata (Demonstration of a new method in the theory of arithmetic), Novi Commentarii Academiae Scientiarum Petropolitanae 8 (1763), 74–104. Eneström index E271. Facsimile at the Euler Archive.

L. Euler, Speculationes circa quasdam insignes proprietates numerorum (Speculations about certain outstanding properties of numbers), Acta Academiae Scientarum Imperialis Petropolitinae 4 (1784), 18–30. Eneström index E564. Latin original and an English translation by J. Bell available at the Euler Archive.

C. F. Gauss, Disquisitiones Arithmeticae. Leipzig: Gerhard Fleischer, 1801. (English translation by A. A. Clarke, Yale University Press, 1965.)

E.R. Tou, “Math Origins: The Totient Function,” Convergence (MAA), September 2017. DOI:\,10.4169/convergence20170923.

R. Wilson, Number Theory: A Very Short Introduction, Oxford University Press, 2020.