Michael Emmerich, January 9, 2025

In this essay, we use the theory of prime vectors (see [1]) to provide an alternative proof of the unique factorization of integers into prime factors: Unlike earlier proofs [4], notably its first proof by Carl Friedrich Gauss [3], this extends unique factorization to rational numbers, and we also establish a one-to-one correspondence between rational numbers and prime vectors.

1. Prime Vectors

In an earlier essay [1], prime vectors were introduced to represent positive rational numbers (). We will provide a brief recap of the definition of prime vectors and then state the theorem and prove it. In particular, we demonstrate that rational numbers can be represented using prime vectors without assuming a priori the Fundamental Theorem of Arithmetic (FTA), and that the mapping

is bijective.

Definition: Prime Vectors for Integers

Let denote the sequence of prime numbers, where

. Any integer

can be expressed as a product of primes:

The existence of such a representation is well known and traces back to Euclid, see for instance for a proof relying only on elementary arithmetic [2].

The exponents are non-negative integers, and only finitely many are nonzero. We define the prime vector of

as the infinite ordered list:

where is the exponent of the prime

in the factorization of

. The space of prime vectors for natural numbers is denoted by

.

Definition: Prime Vectors for Rational Numbers

We extend the definition to positive rational numbers . Any

can be uniquely expressed as:

Here, the exponents are integers (positive, negative, or zero). The prime vector of

is the infinite ordered list:

where is the exponent of the prime

in the factorization of

. The space of prime vectors for rational numbers is denoted by

.

Remark 1 For integers, the exponentsare non-negative (

), whereas for rational numbers, they may be any integer (

).

2. Unique Factorization

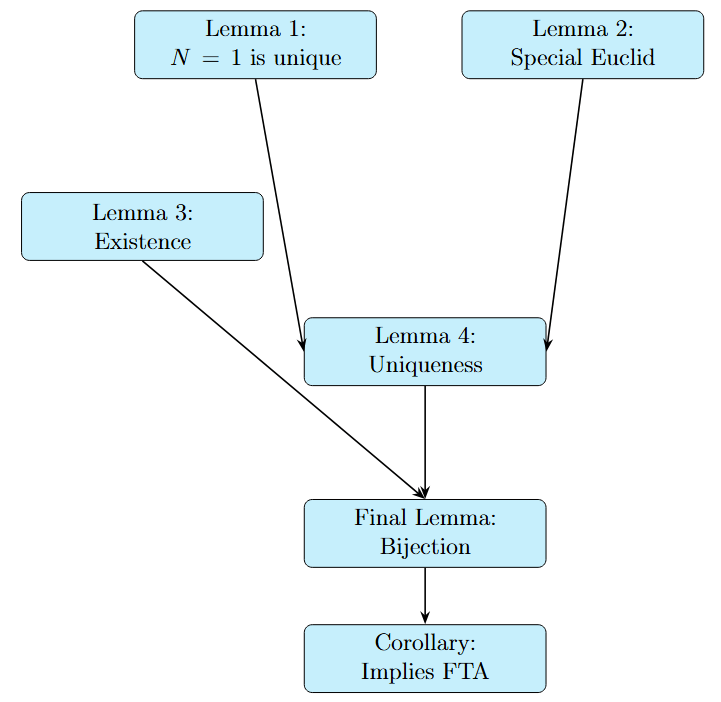

Before proving the theorem on unique factorization of rational numbers we will first proof some auxiliary lemmas.

The figure below highlights the flow of our proof.

Lemma 1 (Unique Representation of.) The number

is represented by the unique prime vector

, corresponding to

.

Proof: We aim to show that can only be represented by the prime vector

.

1. Case: All Exponents are Zero: If , then:

which satisfies the definition of .

2. Case: One or More Exponents are Nonzero: For the product to equal

, the contributions from the positive and negative exponents must perfectly balance:

The left and right products can be renamed to , respectively

and organized as a sorted product of primes where

and

are two non-overlapping multi-sets of primes. Assume, that the primes are sorted by their index in semi-increasing order:

Assume we have chosen the naming and

such that

. The strict inequality follows from the disjoint-ness of the two multi-sets. Then, since

and

is a factor of

, it holds that

must divide

. Since

is prime and

is distinct to all factors

,

cannot divide

. Therefore,

must divide

, due to Euclids lemma. By applying this principle iteratively,

if it divides

must divide

or

. It is impossible for

to divide

because the ordered list shows

and

is prime. This reasoning implies

must divide

, reducing inductively until

, leading to a contradiction.

In the above paragraph, we used Euclid’s lemma to argue that if divides

and

is prime, then

must either divide

or divide

. However, the proof of Euclid’s lemma is quite lengthy and for this proof it suffices to proof a special case of Euclid’s lemma.

Lemma 2 (Special Case of Euclids Lemma.) Letdenote a prime number and

denote a number that is coprime with

and

. If

divides the product

then

must divide

.

Proof: The lemma can be proven using only simple arithmetic by strong induction. Our proof corresponds to a proof of the auxiliary lemma in [2], case 3: We can rewrite the statement divides the product

as the statement: There exists a positive integer

such that

. Now, we subtract

from both sides, which yields

. Since

and

are coprime, also

and

are coprime. Hence, by the induction hypothesis (using

), we obtain that

must divide

or put in other words there exists a positive integer

such that

. Substituting

into

yields

. We divide the latter equation by

, which is positive since

, to obtain

, which proves the result.

Lemma 3 (Existence of Prime Factorizations of Rational Numbers) Every positive rational numberhas a prime vector representation

, with

denoting primes, and

denoting integer exponents.

Proof: Let and

denote positive integers, and

denote the rational number we want to represent through

and

, with

and

. To obtain the factorization, we can use the well-known division tree algorithm [2]. Note that the positive integers are now denoted by a prime vector of

, say

and a prime vector of

, say

. Then we cancel out the terms that refer to the same prime numbers, and this yields

.

Lemma 4 (Uniqueness of Prime Factorizations) Each positive rational numberhas at most one prime factorization, up to the order of the factors.

Proof: Let and suppose

has two distinct factorizations into primes:

where

and

are primes, and

. We aim to show that

,

, and

for all

. Let

denote some prime vector

and

has some prime vector

, respectively. We want to show that, if

, or

then it follows that

. Consider, this is not the case. Then at least for one entry

, and hence

, which contradicts that there is only one unique representation of

as a prime vector in

.

3. Bijection between the Rationals and Prime Vectors

Based on the above unique factorization theorem of the rational numbers we prove the one-to-one correspondence of rational numbers and prime vectors as a corollary.

Lemma 5 (Bijection Between Rational Numbers and Prime Vectors) The mapping, defined by associating each positive rational number

with its unique prime vector

where

and

, is bijective. Specifically:

- For every

, there exists a unique prime vector

.

- For every prime vector

, there exists a unique

.

Proof: Three statements consolidate the proof:

- For every positive rational number there exists a factorization (see Lemma 3)

- For every rational number the factorization is unique (see Lemma 4).

- Every prime-vector represents a rational number. (This is simple; compute the product of prime numbers raised to the exponents given in the prime vector.).

Remark 2 This bijection implies the Fundamental Theorem of Arithmetic (FTA) for positive rational numbers. Specifically, everycan be factored as a product of primes

and this factorization is unique, with exponents

. This extends the classical FTA, which asserts the unique factorization of integers, to the broader domain of rational numbers. We also established the Fundamental Theorem of Arithmetic for positive integers using an alternative approach, beginning with the existence of prime vector representations of positive integers. Our proof relied only on a specific case of Euclid’s lemma. While it can be argued, that a new proof may not be strictly necessary, we believe, as noted also in [4], that presenting alternative proofs can provide valuable insights, helping mathematicians deepen their understanding of the core ideas underpinning the theorem.

- Michael T.M. Emmerich, Playing with primes, emmerix.net July 29, 2024.

- Michael T.M. Emmerich, Fundamental Theorem of Arithmetics: A proof from first principles, emmerix.net December 7, 2024

- Gauss, C. F. (1801). Disquistiones arithmeticae. Dissertation. Königliche Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften zu Göttingen.

- John W. Dawson. Why Prove it Again: Alternative Proofs in Mathematical Practice. Basel: Birkhäuser, 2015.