The Fundamental Theorem of Arithmetic:A Proof from Elementary Principles

Michael Emmerich, December 7th, 2024

The Fundamental Theorem of Arithmetic states that every integer greater than 1 can be uniquely represented as a product of prime numbers, apart from the order of the factors. This essay aims to prove the theorem rigorously from elementary principles, i.e., using only the basic concepts of school-level arithmetic. The proof is not new—I have just written it in my own way. It combines parts of Carl Friedrich Gauss’s proof from his doctoral dissertation and the Lemma of Euclid from the 13th Book of Elements and its modern explanations. I hope this essay succeeds in making the proof clear and easy to understand

1. Foundations and Definitions

Definition 1 (Relatively Prime Pair) Two integersand

are said to be relatively prime if their greatest common divisor (gcd) is 1, i.e.:

This means that

and

do not share any prime factors.

Definition 2 (Prime Number) A prime number is a natural numberthat has exactly two positive divisors, namely 1 and itself. In other words,

is a prime if:

Here, the symbol

means “divides,” indicating that

is a divisor of

. For example,

means that 3 is a divisor of 6.

Definition 3 (Prime Factorization) A prime factorization of an integeris a representation of

as a product of prime numbers:

where

are primes. The order of the factors does not matter since multiplication is commutative.

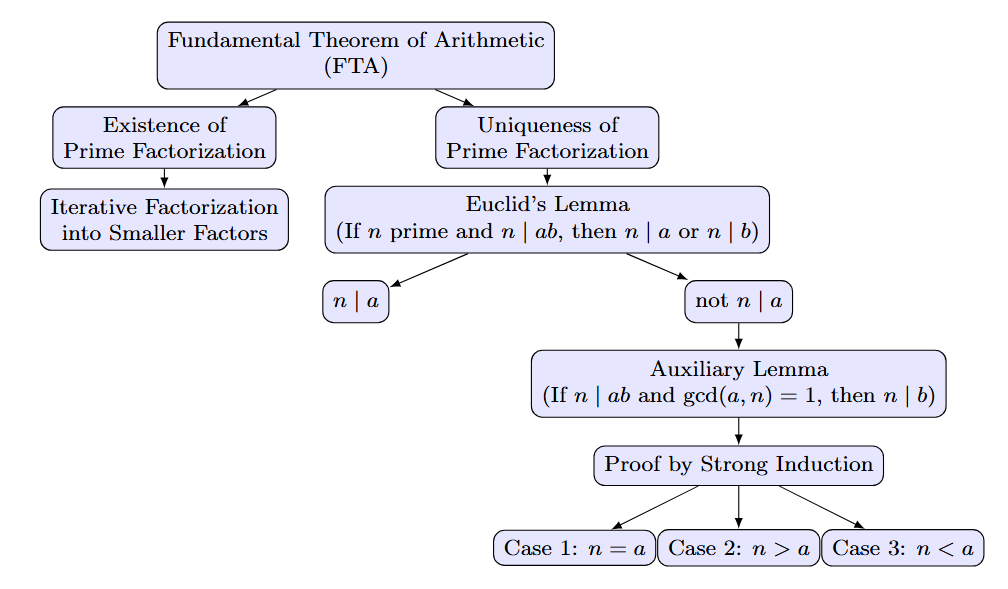

Before we start to go into the details, let us provide an overview of the proof in the following diagram. We will then go through these parts step by step:

2. Proof of Existence

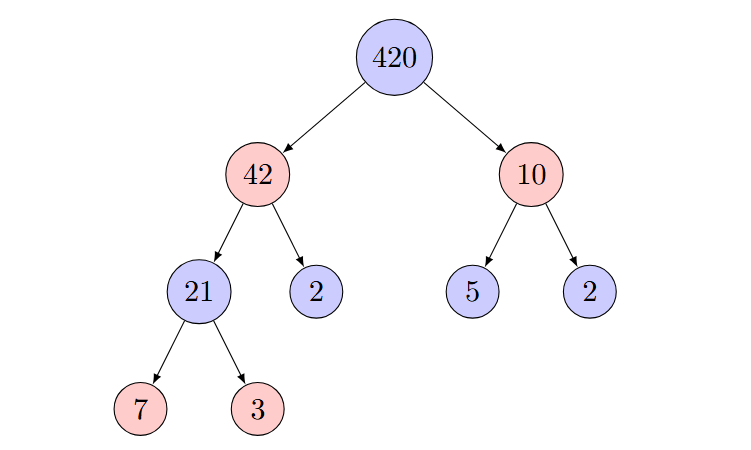

The proof proceeds by a tree-like factorization. Each number is successively factored by dividing it by an arbitrary divisor other than 1 and itself, until only prime numbers remain. This is visualized using the example of the number 420:

In this tree, 420 is successively broken down into factors: first into 10 and 42, then 10 into 5 and 2, while 42 is factored into 21 and 2. Finally, 21 is factored into 7 and 3. Thus, we have:

This method shows that any has at least one factorization that can be continued until only prime factors remain.

3. Proof of Uniqueness

The uniqueness proof is straightforward once one understands Euclid’s lemma, which plays a subtle role in the argument.

3.1. Initial Situation

Consider a number that can be represented as a product of prime factors. Suppose there are two possible representations:

where all and

are prime numbers. We already know that at least one such representation exists.

3.2. Further Course of the Proof

Now we take one of the factors for

. By Euclid’s lemma, we know that at least one of the factors

is divisible by

, say

.

3.3. Division and Reduction

Let us first define .

Now we iterate over all .

Dividing by

, we get:

For the remaining number (after division) , there is also a product representation:

Each time we lose one factor with equal value in both product representations, since (both are prime factors by definition). Therefore when all iterations have finished we will have shown that the factors of both factorizations are the same.

3.4. Proof of the Auxiliary Lemma

Lemma 4 (Auxiliary Lemma) Ifis a positive integer,

, and

, then

.

Proof:

We prove the lemma by strong induction on the product .

Base Case: For , the lemma is trivial, since

implies

.

Inductive Hypothesis: Assume the lemma holds for all products .

Inductive Step: Let and

. We need to show that

. In other words, since

, there exists some

such that

.

We consider three cases:

Case 1: . In this case,

only if

. Trivially,

holds then.

Case 2: . Subtracting

from both sides of

, we get:

Since is coprime

and

, we have

.

(The latter statement holds, because any divisor of both

and

must also divide their sum:

. Therefore, if

divides both

and

, it must also divide

.)

The product is smaller than

because

. By the induction hypothesis,

. Hence, there exists

such that:

Substituting into the reduced equation

, we get:

Since , we can divide by

:

Case 3: . This case is analogous to Case 2. Subtracting

from both sides of

, we have:

Since and

are co-prime,

.

(The latter statement holds, because any divisor of both

and

must also divide their sum:

. Therefore, if

divides both

and

, it must also divide

.)

Again, . By the induction hypothesis,

. Because

and

are relatively prime we can use the induction hypothesis and conclude

. Thus, there exists

:

Substituting into

:

Since , we divide by

:

We have thus found that is a positive integer.

Conclusion: In all cases, it follows that . This completes the proof of the lemma.

Lemma 5 (Euclid’s Lemma) Letbe a prime number. If

, then

or

.

Proof: We prove the lemma by case distinction:

Case 1:

- If

, then from the property of divisibility,

is immediately true. In this case, the statement is trivially satisfied, as

need not be considered.

Case 2:

- If Case 1 does not apply, then

, and also it holds

, since

is prime.

- From this, it follows that

and

are relatively prime, i.e.,

.

- Since

, by the Auxiliary Lemma we conclude that

.

4. Consequences and Applications

The Fundamental Theorem of Arithmetic establishes that each integer greater than 1 can be uniquely represented by its set of prime factors. This uniqueness is not merely theoretical: it forms the basis for much of modern number theory, algebra, and cryptography.

One direct consequence is that positive integers can be encoded as “prime vectors.” That is, if we list all prime numbers in ascending order , every positive integer

can be represented by a vector of exponents corresponding to these primes:

where all but finitely many are zero. This idea is explored in, for example, “Playing with Primes” (2024), which discusses the intuition behind such representations and how factoring integers into their prime bases can be seen as mapping them into an infinite-dimensional vector space over the nonnegative integers and replace multiplication by prime vector addition.

The presented proof has many steps, the validity of each one of them should be easy to check by elementary math. But it would be still desirable to find proofs that work without induction and have less steps.

Alternative proves of the fundamental theorem of arithmetics are provided in Dawson (2015). Notably, the proof can be done by simple mathematics without Euclids argument and without Bezout’s theorem which is also often employed for proving FTA. It remains to be seen if even more simple and intuitive proofs can be found.

Gauss, Carl Friedrich (1966) [1801], Groth, Paul; Bressi, Todd W. (eds.), Disquisitiones Arithmeticae, translated by Clarke, Arthur A., New Haven: Yale, doi:10.12987/9780300194258,; Corrected ed. 1986, New York.

Playing with Primes – Michael Emmerich

Euclid (1956), The Thirteen Books of the Elements, vol. 2 (Books III-IX), translated by Heath, Thomas Little, Dover Publications

Dawson Jr, J. W. (2015). Why prove it again?: Alternative proofs in mathematical practice. Birkhäuser.