Michael Emmerich, JYU, Finland, 28.1.2026

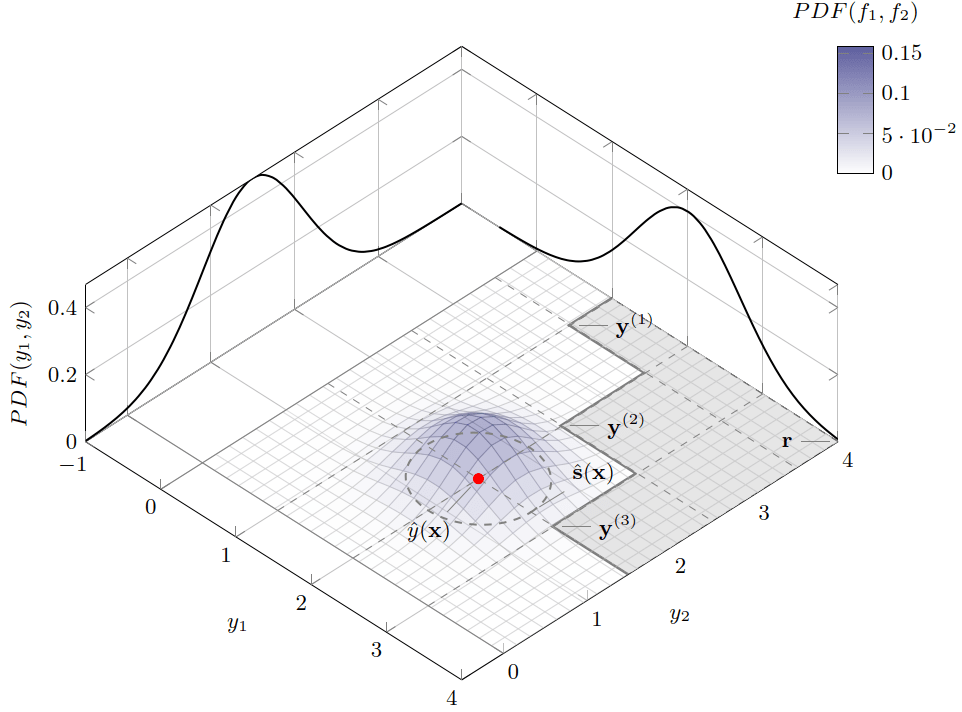

When objective and constraint evaluations are expensive (CFD/FEM, digital-twin simulations, etc.), we often rely on Gaussian process regression (Kriging) as a surrogate. A GP does not only predict a mean vector, it also delivers uncertainty. Interpreted component-wise, this uncertainty naturally forms an axis-aligned confidence box in for

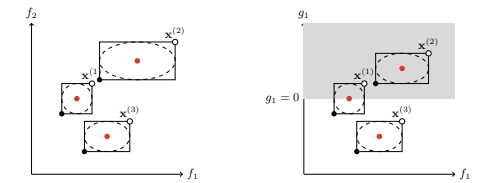

objectives (and similarly for constraints). These boxes enable interval filters: crisp, dominance-based rules that can label candidates as certainly reject, possibly reject, or “keep for consideration,” before spending a single true evaluation.

The core ideas go back to my 2005 PhD thesis (Emmerich, 2005) and were worked out for surrogate-assisted multiobjective selection and constraint handling in early 2004-era papers (see references at the end). A compact discussion of the interval-filter logic is also included in the attached book chapter (Section “Interval Filters,” with the illustrative figure of boxes in objective space and constraint space).

From GP/Kriging prediction to a “confidence box”

Assume minimization of objectives. For a candidate decision vector

, a GP provides a predictive mean

and predictive standard deviations

(component-wise, or from a diagonal approximation). Pick a width parameter

(e.g., tied to a desired coverage under a Gaussian assumption). Define lower/upper bounds per objective:

and

.

Geometrically, the candidate is associated with the axis-aligned box . In selection, this turns uncertain vectors into comparable objects: boxes.

Pareto dominance, now “lifted” to boxes

Recall (minimization): dominates

if

for all

and strict inequality holds for at least one component.

With boxes, we ask: can dominance be concluded for sure, or is it only possible depending on how the true values realize inside the boxes?

Certainly reject (certain dominance)

Let be a candidate with bounds

, and let

be another solution with bounds

(or a fully evaluated point, in which case

).

A simple certain dominance test is:

if dominates

,

then

is certainly dominated and can be labeled certainly reject.

Intuition: even if realizes at its best-case corner (

) and

realizes at its worst-case corner (

),

still wins. So

cannot be non-dominated.

Possibly reject (possible dominance)

A weaker, “there exists a realization” test is:

if dominates

,

then

is possibly dominated (in fact, dominated even under a very favorable realization for

). More generally, if some realization inside the boxes allows

to dominate

, we call

possibly reject.

In practice, “possibly reject” is a tuning knob: using it aggressively increases precision (fewer poor evaluations) but risks losing recall (discarding candidates that could have been among the best). Interval filters make this trade-off explicit (often discussed as error types in pre-selection).

Constrained problems: certain vs possible feasibility

Now add inequality constraints for

. Train surrogate(s) for constraints as well, producing bounds

and

in the same way as for objectives.

-

Certainly feasible: for all

,

.

-

Certainly infeasible (hence certainly reject w.r.t. feasibility): for some

,

.

- Possibly feasible: otherwise (the confidence interval crosses the boundary for at least one constraint).

A clean constrained-Pareto filter can then be phrased as: (i) reject everything that is certainly infeasible; (ii) among the remaining candidates, use box-dominance tests (above) but prioritize certainly feasible solutions over possibly feasible ones. This is exactly the kind of “interval picture” shown in the objective/constraint panels of the interval-filter figure in the attached chapter.

Where this fits in  selection

selection

Consider we want to shortlist a list that comprises the best out of a list of

candidates. We can again apply possibilistic logic to maximize precision or to maximize recall based on the bounding boxes for the epistemic uncertainty.

In a $(\mu+\lambda)$ evolution strategy (or any EA with parent+offspring elitist selection), we routinely have many offspring proposals

but can only afford to truly evaluate a small subset. Interval filters act as a dominance-based pre-screen:

- Use GP/Kriging to assign a confidence box to each offspring (and optionally to unevaluated parents).

- Apply certainly reject rules first (certain infeasibility and certain dominance).

- From the remaining set, keep “possibly non-dominated / not certainly rejected” candidates for actual evaluation or for the next ranking stage (e.g., non-dominated sorting, hypervolume contribution, or exploration heuristics). The details for this step and are described in the attached PDF of a preprint.

The key point: GP/Kriging uncertainty is not just “error bars.” Treated as an -D confidence box, it gives logic-level statements (“cannot win”, “might win”) that are directly compatible with Pareto dominance and constraint satisfaction.

- M. Emmerich. Single- and Multi-Objective Evolutionary Design Optimization Assisted by Gaussian Random Field Metamodels. PhD thesis, University of Dortmund, 2005.

- M. Emmerich. Python implementation of dynamic programming for minimum Riesz s-energy subset selection in ordered point sets. Zenodo, 10.5281/zenodo.14792491, 2025.

- M. Emmerich, N. Beume, and B. Naujoks. An EMO algorithm using the hypervolume measure as selection criterion. In International Conference on Evolutionary Multi-Criterion Optimization, pages 62–76. Springer, 2005.

- M. Emmerich, K. C. Giannakoglou, and B. Naujoks. Single- and multiobjective evolutionary optimization assisted by Gaussian random field metamodels. IEEE Transactions on Evolutionary Computation, 10(4):421–439, 2006.

- M. Emmerich, A. Giotis, M. Özdemir, T. Bäck, and K. Giannakoglou. Metamodel-assisted evolution strategies. In International Conference on Parallel Problem Solving from Nature, pages 361–370. Springer, 2002.

- M. Emmerich and B. Naujoks. Metamodel assisted multiobjective optimisation strategies and their application in airfoil design. In Adaptive Computing in Design and Manufacture VI, pages 249–260. Springer, 2004.

- M. Emmerich and B. Naujoks. Metamodel-assisted multiobjective optimization with implicit constraints and its application in airfoil design. In International Conference & Advanced Course ERCOFTAC, Athens, Greece, 2004.

- Limbourg, P., & Aponte, D. E. S. (2005, September). An optimization algorithm for imprecise multi-objective problem functions. In 2005 IEEE Congress on evolutionary computation (Vol. 1, pp. 459-466). IEEE.

- M. T. M. Emmerich. Early ideas and innovations in Bayesian and model-assisted multiobjective optimization. In Challenges in Design Methods, Numerical Tools and Technologies for Sustainable Aviation, Transport and Industry, pp. 93–116, First Online: 28 January 2026. (Computational Methods in Applied Sciences, vol. 17). (Featured Article)https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-98675-8_8