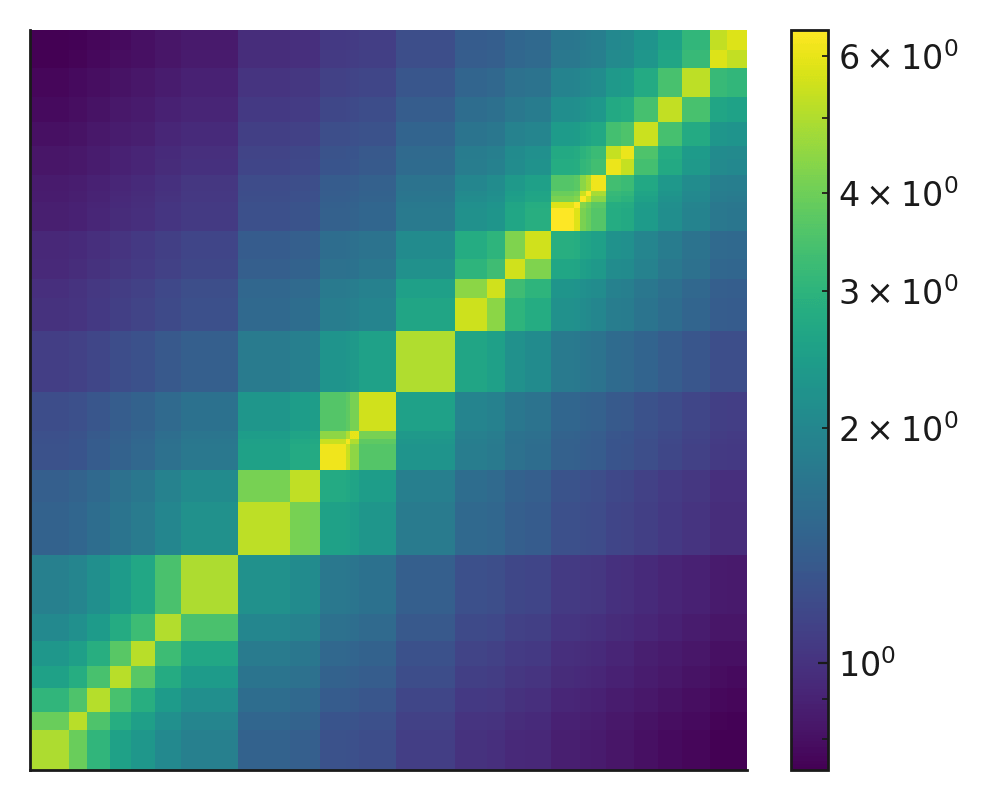

Figure: Logarithmically scaled Riesz interaction matrix for a random set of 30 points on the unit interval,

with cell sizes proportional to the distances between points. Each rectangle corresponds to a pair of points:

darker cells indicate stronger interactions (points that are closer on the line), while lighter cells indicate

weaker interactions. Off-diagonal entries show

for

, and diagonal entries show

,

the log-transformed per-point contribution to the total Riesz

-energy with

.

Some questions in computational geometry are famously hard to solve, even in one dimension:

the classical set partition problem is NP-hard. But here is a different kind of puzzle:

a simple-to-state optimisation problem for which it seems hard even to decide whether it is hard.

Standard polynomial-time methodologies appear to fail, yet there are also structural reasons

to believe that a clever polynomial-time algorithm might exist.

This post is about that borderline case: the one-dimensional Riesz -energy subset selection problem.

Riesz energy and ‘poppy-seed’ problems

Riesz energies sit at the crossroads of analysis, numerical methods, and discrete geometry. The monograph by Borodachov, Hardin, and Saff, Discrete Energy on Rectifiable Sets, develops a general theory of point configurations that minimise Riesz-type energies on manifolds and rectifiable sets (Borodachov, Hardin, and Saff, 2019). Minimal Riesz energy configurations are often used as models for point sets that are evenly spread over a domain. In numerical analysis and approximation, so-called “poppy seed” algorithms generate (near-)minimal Riesz energy configurations to distribute points quasi-uniformly across manifolds or unions of manifolds: each point behaves like a repelling particle, and the system relaxes into an approximately even configuration (Borodachov, Hardin, and Saff, 2007).

Formally, for a finite set of points in a metric space

and a subset

of size

, the Riesz

-energy is

where controls how strongly we penalise short distances.

Intuitively, each pair of points repels with strength

:

very close points contribute a large penalty, while distant points contribute little.

Minimising

over subsets

therefore promotes well-separated, “evenly spread” point sets

(Borodachov, Hardin, and Saff, 2019).

Hardness in general metric spaces

When we move to general metric spaces (or higher-dimensional Euclidean spaces),

selecting a minimum-energy subset of points from

candidates becomes

algorithmically difficult.

Pereverdieva et al. (2025) showed that

the Riesz

-Energy Subset Selection Problem is NP-hard in general metric spaces:

even deciding whether there exists a subset with energy at most a given threshold

is NP-hard under standard complexity assumptions (Pereverdieva et al., 2025).

The high-level reason is that, with enough geometric freedom, the pairwise terms

can be arranged so that low-energy subsets encode

solutions to classical NP-hard combinatorial problems.

The 1-D restriction: simple geometry, dense interactions

Now specialise to a very structured situation:

- All candidate points lie on the real line, sorted as

.

- We want to pick exactly

of them to minimise

.

The decision version of the problem can be phrased as:

From a geometric viewpoint, this looks friendly: the points form a path of tree-width 1, and many one-dimensional optimisation problems admit efficient dynamic programming or greedy algorithms once everything is sorted.

But the Riesz energy couples every pair of selected points.

If , the interaction graph on these

points is a clique:

each pair contributes a term

to the energy.

So while the underlying geometry is a path, the induced interaction structure has tree-width

.

This rules out the most straightforward tree-width–based dynamic programming approaches.

A simple way to see this is to imagine taking any candidate subset and building a graph whose

vertices are the points in

and whose edges represent the pairwise interactions.

This graph is always the complete graph on

vertices.

Any exact dynamic programme that treats each pairwise interaction as a local potential in a tree-decomposition

must therefore handle bags of size proportional to

, not a fixed constant.

Thus, a polynomial-time algorithm, if it exists, cannot rely solely on “small tree-width” arguments.

Dynamic programming on the line: close, but not quite

A natural idea is to exploit the ordering via dynamic programming:

we process points from left to right, and at each step we decide whether to include

,

updating the energy accordingly.

A recent arXiv paper describes exactly such a dynamic programming approach for

ordered point sets on the line, and extends it to 2-D Pareto fronts arising in

biobjective optimisation (Emmerich, 2025).

The algorithm exploits the 1-D structure to construct near-minimising subsets in time

and clearly outperforms naive greedy selection on many examples.

However, because the exact Riesz energy involves all pairwise interactions, the algorithm cannot keep a complete history of all previous choices in a small state. Instead, it compresses or approximates far-field interactions. As a consequence, the scheme is not guaranteed to find the global minimum: for some carefully chosen examples, the dynamic programme and a brute-force search return slightly different solutions.

In other words, dynamic programming in 1-D is a powerful heuristic and often behaves “as if” the problem were polynomial-time solvable, but we do not yet have a proof that it yields an exact polynomial-time algorithm for the one-dimensional Riesz subset selection problem.

Why NP-hardness is also hard to prove in 1-D

If we try to go the other way and prove NP-hardness in 1-D, we immediately run into the rigidity of the real line. Most hardness proofs for Riesz-type subset selection in higher dimensions rely on geometric gadgets: variables, wires, and clauses embedded in the plane so that specific distances encode logical constraints.

In one dimension, all candidate points must lie on a single line.

This severely constrains which patterns of pairwise distances can occur.

For example, four points on a line cannot realise an arbitrary N times N table of distances,

whereas in higher dimensions they often can.

This makes it difficult to encode general quadratic interaction patterns or to isolate

gadget interactions while bounding everything else.

A successful NP-hardness construction in 1-D would likely need a sophisticated multi-scale arrangement of points on the line, carefully balancing:

- very small distances (huge Riesz penalties) to enforce local constraints,

- intermediate scales to encode weights or combinatorial choices, and

- very large distances so that far-field interactions remain controlled.

At the same time, such a construction must respect the linear order of the real line and keep all coordinates polynomially bounded in the input size. Designing such a reduction with only one degree of geometric freedom (the ordering of the points) is technically demanding, and no such construction is currently known.

A borderline problem — and an invitation

To summarise:

- In general metric spaces, minimum Riesz

-energy subset selection is NP-hard (Pereverdieva et al., 2025).

- In one dimension, ordering and convexity suggest dynamic programming and other polynomial-time techniques, and there is already a promising DP-based heuristic that works very well in practice (Emmerich, 2025).

- Yet, we lack both an exact polynomial-time algorithm and a proof of NP-hardness for the one-dimensional case.

The one-dimensional Riesz -energy subset selection problem therefore sits

in an intriguing grey zone: it is easy to formulate, deeply connected to “poppy seed”

point distributions and manifold sampling, and clearly NP-hard in higher dimensions,

but its exact complexity in 1-D remains elusive.

This situation is reminiscent of another famous story in mathematical physics: the Ising model. While finding ground states of general Ising spin systems is NP-hard in three or more dimensions and on general graphs, Onsager’s celebrated solution of the two-dimensional nearest-neighbour Ising model on the square lattice provided an exact and non-trivial analytic solution for the partition function and critical behaviour in that special case (Onsager, 1944). It shows that sometimes, a carefully structured low-dimensional version of a seemingly intractable problem admits a beautiful, unexpected closed-form solution (Domb, 1974).

Maybe the one-dimensional Riesz -energy subset selection problem hides a similar surprise.

Is it NP-hard even on the line, or does there exist an elegant polynomial-time algorithm waiting to be discovered?

If you have ideas for reductions, clever dynamic programmes, or structural theorems,

you are invited to think about this puzzle and, perhaps, help resolve the complexity

of one of the simplest-to-state yet currently unresolved optimisation problems arising from Riesz energy.

References

- Borodachov, S. V., Hardin, D. P., and Saff, E. B. (2019). Discrete Energy on Rectifiable Sets. Springer Monographs in Mathematics, Springer.

- Borodachov, S. V., Hardin, D. P., and Saff, E. B. (2007). “Asymptotics for Discrete Weighted Minimal Riesz Energy Problems on Rectifiable Sets,” Communications in Mathematical Physics 274, 399–430.

-

Pereverdieva, K., Emmerich, M. T. M., Deutz, A. H., Ezendam, T., Bäck, T., and Hofmeyer, H. (2025).

“Comparative Analysis of Indicators for Multiobjective Diversity Optimization,”

in Evolutionary Multi-Criterion Optimization (EMO 2025), Springer.

Includes a proof that the Riesz

-Energy Subset Selection Problem is NP-hard in general metric spaces.

-

Emmerich, M. T. M. (2025).

“Minimum Riesz

-Energy Subset Selection in Ordered Point Sets via Dynamic Programming,” arXiv:2502.01163.

- Onsager, L. (1944). “Crystal Statistics. I. A Two-Dimensional Model with an Order-Disorder Transition,” Physical Review 65(3–4), 117–149.

- Domb, C. (1974). “Ising model,” in Phase Transitions and Critical Phenomena, Vol. 3, eds. C. Domb and M. S. Green, Academic Press.

Please cite as:

Michael Emmerich (2025, December 8). The Hardness of Proving Hardness: Selecting Minimum Riesz Energy Subsets on a Line. Mathematical Playground (www.emmerix.net).