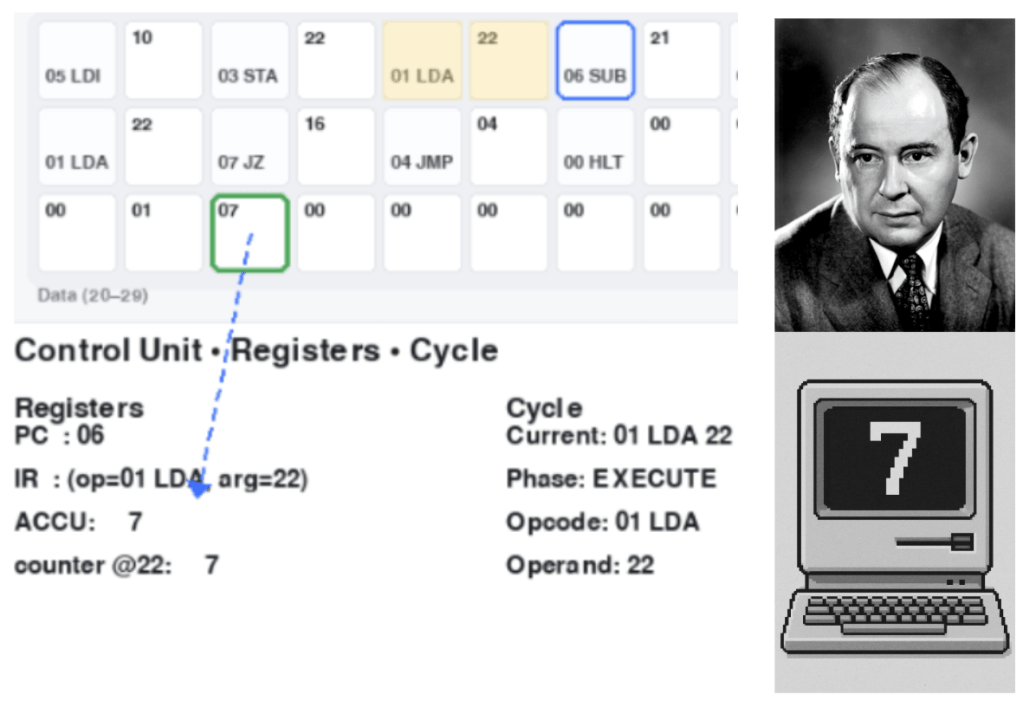

This interactive mini-simulation shows a stored-program computer in the classic von Neumann style executing a tiny machine-code program that counts down from 10 to 0. You can watch the registers and memory interact during the fetch–decode–execute cycle. It’s a compact demonstration of the model that underlies almost all modern computing—right up to the CPUs and GPUs that run today’s AI systems.

How to use it

- Space — pause / resume

- → — single-step one micro-operation

- R — reset the program

Registers and Abbreviations

A few key registers are displayed in the panel:

- PC (Program Counter): holds the address of the next instruction to fetch.

- IR (Instruction Register): stores the current instruction (opcode and operand).

- ACC (Accumulator): the main working register for arithmetic and logic.

The program also uses a counter stored in memory cell [22], which is decremented each loop.

Instruction Set (Opcodes and Mnemonics)

Each instruction consists of an opcode (a number) and an operand (a memory address or value). The simulation uses a very small instruction set:

| Opcode | Mnemonic | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | HLT | Halt execution |

| 1 | LDA a | Load ACC from memory address a |

| 2 | ADD a | Add mem[a] to ACC |

| 3 | STA a | Store ACC into memory address a |

| 4 | JMP a | Jump to address a unconditionally |

| 5 | LDI v | Load immediate value v into ACC |

| 6 | SUB a | Subtract mem[a] from ACC |

| 7 | JZ a | If ACC = 0, jump to address a |

The Countdown Program

The code below shows how the countdown is achieved. It starts by loading the number 10, storing it in [22],

then repeatedly subtracting 1 (from [21]) until the counter reaches 0.

00: LDI 10 ; ACC ← 10 02: STA 22 ; counter ← 10 04: LDA 22 ; ACC ← counter 06: SUB 21 ; ACC ← ACC - 1 08: STA 22 ; counter ← ACC 10: LDA 22 ; ACC ← counter 12: JZ 16 ; if ACC == 0, jump to HALT 14: JMP 04 ; loop back to subtract again 16: HLT 00 ; stop

An interesting question for reviewing your understanding would be how to change this program to one that counts from 1 to 10.

Why this matters (and how it links to AI)

This simple loop is representative of how real processors run every program: a stream of numeric opcodes acting on data in memory. Modern AI workloads (from Python frameworks to CUDA kernels) are ultimately translated into such instruction streams for CPUs/GPUs that still follow the same stored-program principle—albeit with many layers of caching, pipelining, and parallelism.

Historical context

The stored-program concept was articulated in John von Neumann’s 1945 First Draft of a Report on the Electronic Discrete Variable Automatic Computer (EDVAC), which described a machine with a memory holding both code and data, a central arithmetic unit, and a control unit.¹ The idea rapidly influenced post-war computer design and is often summarized as the von Neumann architecture.² The first electronic stored-program to run successfully executed on the Manchester “Baby” on 21 June 1948, demonstrating the approach in practice.³

- John von Neumann, First Draft of a Report on the EDVAC (1945). See e.g. MIT/STS scan: PDF.

- Overview of the stored-program concept: Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Manchester Baby (Small-Scale Experimental Machine) — first stored-program run, 21 June 1948: University of Manchester.